How to use the linux sleep command to pause a bash script

Содержание:

- Description

- How to use the Linux sleep command to pause a bash script

- Sleep command syntax:

- Modifying or removing a trap

- Running Linux Bash scripts in background mode

- Scheduling a job

- Scheduling scripts

- Description

- How to Use the Sleep Command

- So, what does the sleep command do in Linux?

- Return Value

- COLOPHON top

- DESCRIPTION top

- NOTES top

- Description

- How to pause my bash shell script for 10 second before continuing

- Rationale

- Bash add pause prompt in a shell script with bash pause command

- Итоги

Description

Real time and process time

-

Real time is defined as time measured from some fixed point, either from a standard point in the past (see the description of the Epoch and calendar

time below), or from some point (e.g., the start) in the life of a process (elapsed time).

Process time is defined as the amount of CPU time used by a process. This is sometimes divided into user and system components. User

CPU time is the time spent executing code in user mode. System CPU time is the time spent by the kernel executing in system mode on behalf of the process

(e.g., executing system calls). The time(1) command can be used to determine the amount of CPU time consumed during the execution of a program. A

program can determine the amount of CPU time it has consumed using times(2), getrusage(2), or clock(3).

The hardware clock

- Most computers have a (battery-powered) hardware clock which the kernel reads at boot time in order to initialize the software clock. For further details,

see rtc(4) and hwclock(8).

The software clock, HZ, and jiffies

- The accuracy of various system calls that set timeouts, (e.g., select(2), sigtimedwait(2)) and measure CPU time (e.g., (2)) is

limited by the resolution of the software clock, a clock maintained by the kernel which measures time in jiffies. The size of a jiffy is

determined by the value of the kernel constant HZ.

The value of HZ varies across kernel versions and hardware platforms. On i386 the situation is as follows: on kernels up to and including 2.4.x, HZ

was 100, giving a jiffy value of 0.01 seconds; starting with 2.6.0, HZ was raised to 1000, giving a jiffy of 0.001 seconds. Since kernel 2.6.13, the HZ value

is a kernel configuration parameter and can be 100, 250 (the default) or 1000, yielding a jiffies value of, respectively, 0.01, 0.004, or 0.001 seconds. Since

kernel 2.6.20, a further frequency is available: 300, a number that divides evenly for the common video frame rates (PAL, 25 HZ; NTSC, 30 HZ).

The (2) system call is a special case. It reports times with a granularity defined by the kernel constant USER_HZ. User-space

applications can determine the value of this constant using sysconf(_SC_CLK_TCK).

High-resolution timers

- Before Linux 2.6.21, the accuracy of timer and sleep system calls (see below) was also limited by the size of the jiffy.

Since Linux 2.6.21, Linux supports high-resolution timers (HRTs), optionally configurable via CONFIG_HIGH_RES_TIMERS. On a system that supports HRTs,

the accuracy of sleep and timer system calls is no longer constrained by the jiffy, but instead can be as accurate as the hardware allows (microsecond accuracy

is typical of modern hardware). You can determine whether high-resolution timers are supported by checking the resolution returned by a call to

clock_getres(2) or looking at the «resolution» entries in /proc/timer_list.

HRTs are not supported on all hardware architectures. (Support is provided on x86, arm, and powerpc, among others.)

The Epoch

- UNIX systems represent time in seconds since the Epoch, 1970-01-01 00:00:00 +0000 (UTC).

A program can determine the calendar time using gettimeofday(2), which returns time (in seconds and microseconds) that have elapsed since the

Epoch; time(2) provides similar information, but only with accuracy to the nearest second. The system time can be changed using

settimeofday(2).

Broken-down time

- Certain library functions use a structure of type tm to represent broken-down time, which stores time value separated out into distinct

components (year, month, day, hour, minute, second, etc.). This structure is described in ctime(3), which also describes functions that convert between

calendar time and broken-down time. Functions for converting between broken-down time and printable string representations of the time are described in

(3), strftime(3), and strptime(3).

Sleeping and setting timers

- Various system calls and functions allow a program to sleep (suspend execution) for a specified period of time; see nanosleep(2),

clock_nanosleep(2), and sleep(3).

Various system calls allow a process to set a timer that expires at some point in the future, and optionally at repeated intervals; see alarm(2),

getitimer(2), timerfd_create(2), and timer_create(2).

Timer slack

- Since Linux 2.6.28, it is possible to control the «timer slack» value for a thread. The timer slack is the length of time by which the kernel may delay the

wake-up of certain system calls that block with a timeout. Permitting this delay allows the kernel to coalesce wake-up events, thus possibly reducing the

number of system wake-ups and saving power. For more details, see the description of PR_SET_TIMERSLACK in prctl(2).

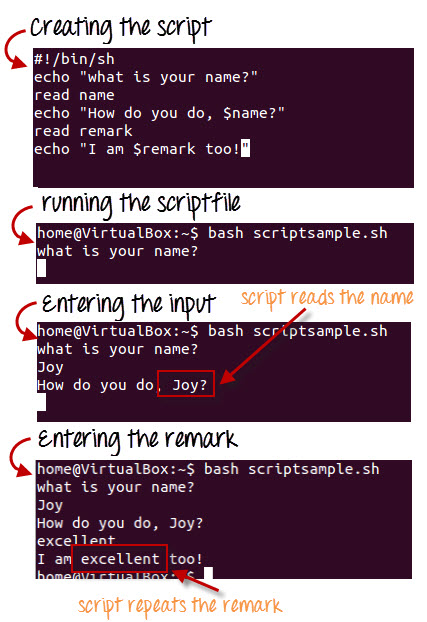

How to use the Linux sleep command to pause a bash script

Let us see a simple example that pause script for 10 seconds.

#!/bin/bash

# Name: sleep-demo.sh

# Purpose: bash script examples that demos sleep command

# Author: Vivek Gite {https://www.cyberciti.biz}

# -----------------------------------------------------------

SLEEP_TIME="10"

echo "Current time: $(date +%T)"

echo "Hi, I'm sleeping for ${SLEEP_TIME} seconds ..."

sleep ${SLEEP_TIME}

echo "All done and current time: $(date +%T)"

|

Run it as follows (see how to run shell script in Linux for more information):

Sleep command in action

sleep command shell script examples

The shell script will start by showing current time on screen. After that, our shell script tells you how to quit and will continue to display current time on screen:

#!/bin/bash

## run while loop to display date and hostname on screen ##

while :

do

clear

tput cup 5 5

echo "$(date) "

tput cup 6 5

sleep 1

done

|

Sleep command syntax:

sleep number

You can use any integer or fractional number as time value. Suffix part is optional for this command. If you omit suffix then time value is calculated as seconds by default. You can use s, m, h and d as suffix value. The following examples show the use of sleep command with different suffixes.

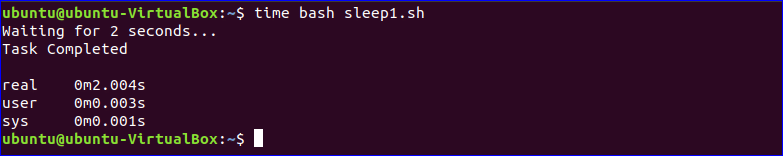

Example-1: sleep command without any suffix

In the following script, sleep command is used with numeric value 2 only and no suffix is used. So, if you run the script then the string “Task completed” will print after waiting for 2 seconds.

#!/bin/bash

echo «Waiting for 2 seconds…»sleep 2echo «Task Completed»

Run the bash file with time command to show the three types of time values to run the script. The output shows the time used by a system, user and real time.

$ time bash sleep1.sh

Output:

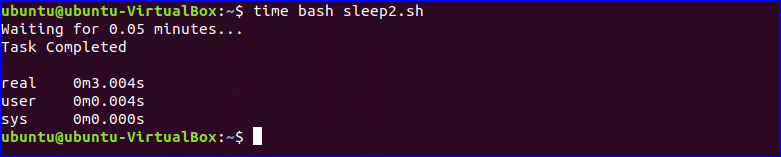

Example-2: sleep command with a minute suffix

In the following script, ‘m‘ is used as the suffix with sleep command. Here, the time value is 0.05 minutes. After waiting 0.05 minutes, “Task completed” message will be printed.

#!/bin/bash

echo «Waiting for 0.05 minutes…»sleep 0.05mecho «Task Completed»

Run the script with time command like the first example.

$ time bash sleep2.sh

Output:

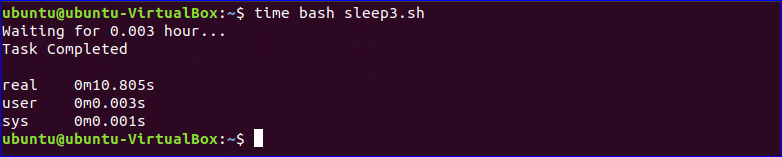

Example-3: sleep command with hour suffix

In the following script, ‘h‘ is used as the suffix with sleep command. Here, the time value is 0.003 hour. After waiting 0.003 hour “Task completed” should be printed on the screen but it requires more times in reality when ‘h’ suffix is used.

#!/bin/bash

echo «Waiting for 0.003 hours…»sleep 0.003hecho «Task Completed»

$ time bash sleep3.sh

Output:

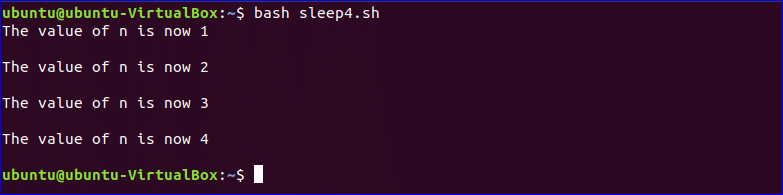

Example-4: sleep command with loop

You can use sleep command for various purposes. In the following example, sleep command is used with while loop. Initially, the value of the variable n is set to 1 and the value of n will be incremented by 1 for 4 times in every 2 seconds interval. So, when will you run the script, each output will appear after waiting 2 seconds.

#!/bin/bashn=1while $n -lt 5 doecho «The value of n is now $n»sleep 2secho » «((n=$n+1))done

Output:

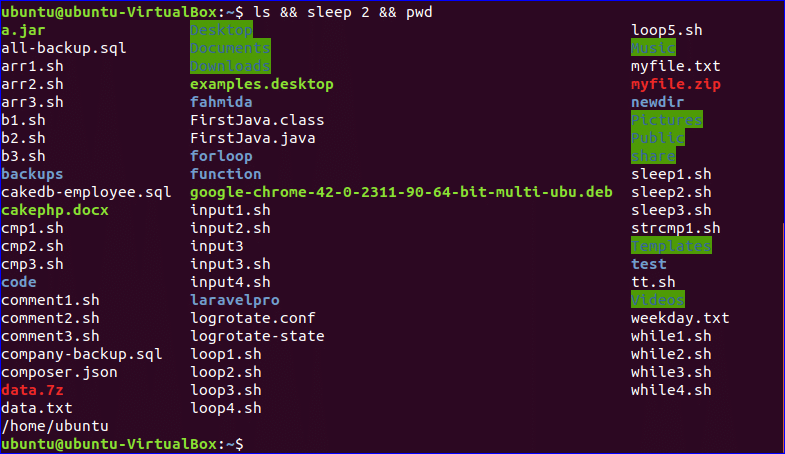

Example-5: sleep command in the terminal with other commands

Suppose, you want to run multiple commands and set the fixed time interval between the outputs of two commands, then you can use sleep command to do that task. In this example, the command ls and pwd are with sleep command. After executing the command, ls command will show the directory list of the current directory and show the current working directory path after waiting for 2 seconds.

$ ls && sleep 2 && pwd

Output:

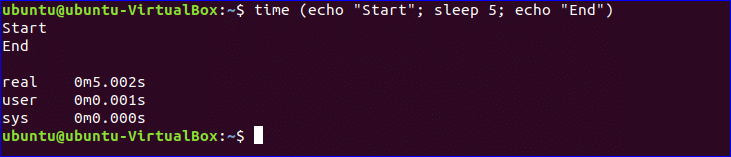

Example-6: Using sleep command from the command prompt

sleep command is used between two echo commands in the following example. Three time values will be displayed after executing the command.

$ time (echo «Start»; sleep 5; echo «End»)

Output:

sleep command is a useful command when you need to write a bash script with multiple commands or tasks, the output of any command may require a large amount of time and other command need to wait for completing the task of the previous command. For example, you want to download sequential files and next download can’t be started before completing the previous download. In this case, it is better to sleep command before each download to wait for the fixed amount of time.

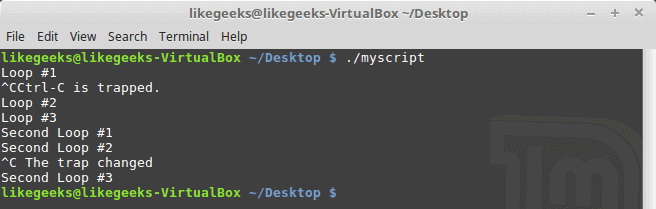

Modifying or removing a trap

You can reissue the trap command with new options like this:

#!/bin/bash trap "echo 'Ctrl-C is trapped.'" SIGINT total=1 while ; do echo "Loop #$total" sleep 2 total=$(($total + 1)) done # Trap the SIGINT trap "echo ' The trap changed'" SIGINT total=1 while ; do echo "Second Loop #$total" sleep 1 total=$(($total + 1)) done

Notice how the script manages the signal after changing the signal trap.

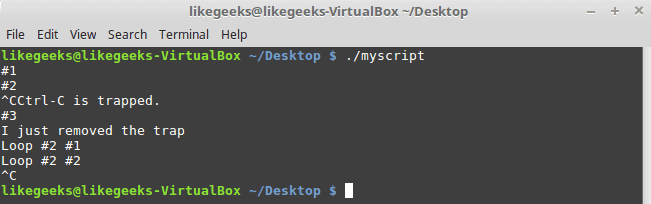

You can also remove a trap by using two dashes.

trap -- SIGNAL

#!/bin/bash trap "echo 'Ctrl-C is trapped.'" SIGINT total=1 while ; do echo "#$total" sleep 1 total=$(($total + 1)) done trap -- SIGINT echo "I just removed the trap" total=1 while ; do echo "Loop #2 #$total" sleep 2 total=$(($total + 1)) done

Notice how the script processes the signal before removing the trap and after removing the trap.

$ ./myscript

Crtl+C

The first Ctrl+C was trapped, and the script continues running while the second one exits the script because the trap was removed.

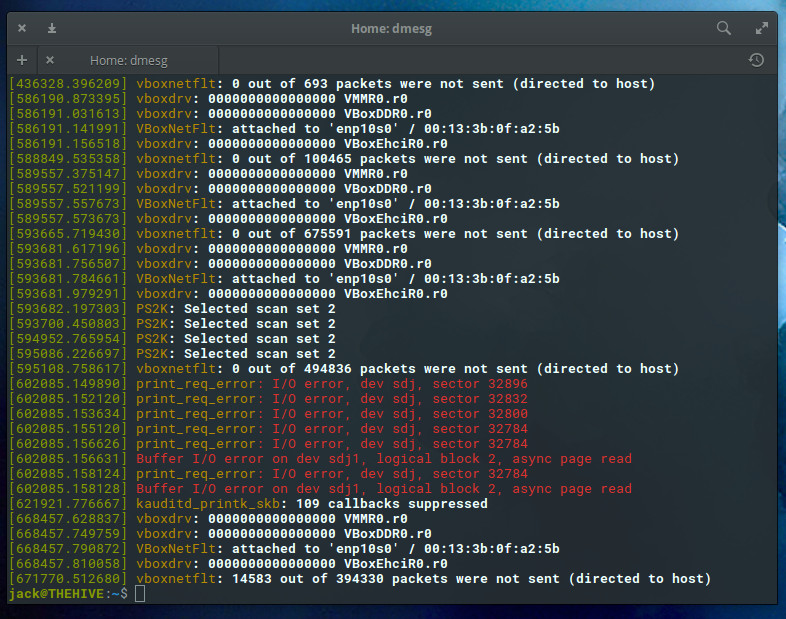

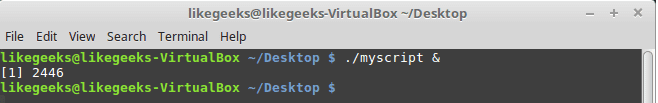

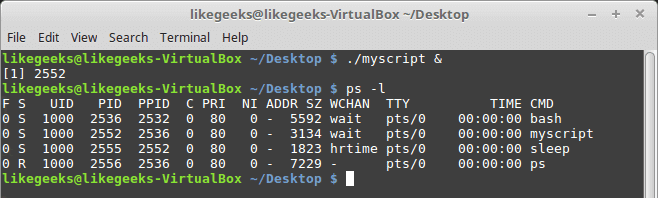

Running Linux Bash scripts in background mode

If you see the output of the ps command, you will see all the running processes in the background and not tied to the terminal.

We can do the same, just place ampersand symbol (&) after the command.

#!/bin/bash total=1 while ; do sleep 2 total=$(($total + 1)) done

$ ./myscipt &

Once you’ve done that, the script runs in a separate background process on the system, and you can see the process id between the square brackets.

When the script dies, you will see a message on the terminal.

Notice that while the background process is running, you can use your terminal monitor for STDOUT and STDERR messages, so if an error occurs, you will see the error message and normal output.

The background process will exit if you exit your terminal session.

So what if you want to continue running even if you close the terminal?

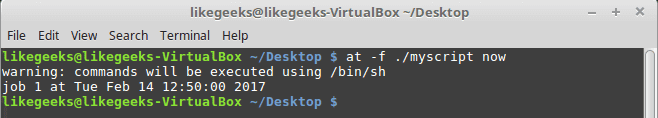

Scheduling a job

The Linux system provides two ways to run a bash script at a predefined time:

- at command.

- cron table.

The at command

This is the format of the command

at time

The at command can accept different time formats:

- Standard time format like 10:15.

- An AM/PM indicator like 11:15 PM.

- A named time like now, midnight.

You can include a specific date, using some different date formats:

- A standard date format, such as MMDDYY or DD.MM.YY.

- A text date, such as June 10 or Feb 12, with or without the year.

- Now + 25 minutes.

- 05:15 AM tomorrow.

- 11:15 + 7 days.

We don’t want to dig deep into the at command, but for now, just make it simple.

$ at -f ./myscript now

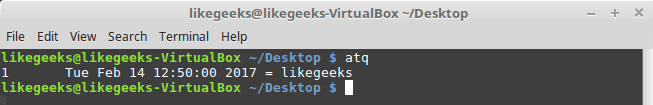

To list the pending jobs, use the atq command:

Scheduling scripts

What if you need to run a script at the same time every day or every month or so?

You can use the crontab command to schedule jobs.

To list the scheduled jobs, use the -l parameter:

$ crontab –l

The format for crontab is:

minute,hour, dayofmonth, month, and dayofweek

So if you want to run a command daily at 10:30, type the following:

30 10 * * * command

The wildcard character (*) used to indicate that the cron will execute the command daily on every month at 10:30.

To run a command at 5:30 PM every Tuesday, you would use the following:

30 17 * * 2 command

The day of the week starts from 0 to 6, where Sunday=0 and Saturday=6.

To run a command at 10:00 on the beginning of every month:

00 10 1 * * command

The day of the month is from 1 to 31.

Let’s keep it simple for now, and we will discuss the cron in great detail in future posts.

To edit the cron table, use the -e parameter like this:

crontab –e

Then type your command like the following:

30 10 * * * /home/likegeeks/Desktop/myscript

This will schedule our script to run at 10:30 every day.

Note: sometimes, you see error says Resource temporarily unavailable.

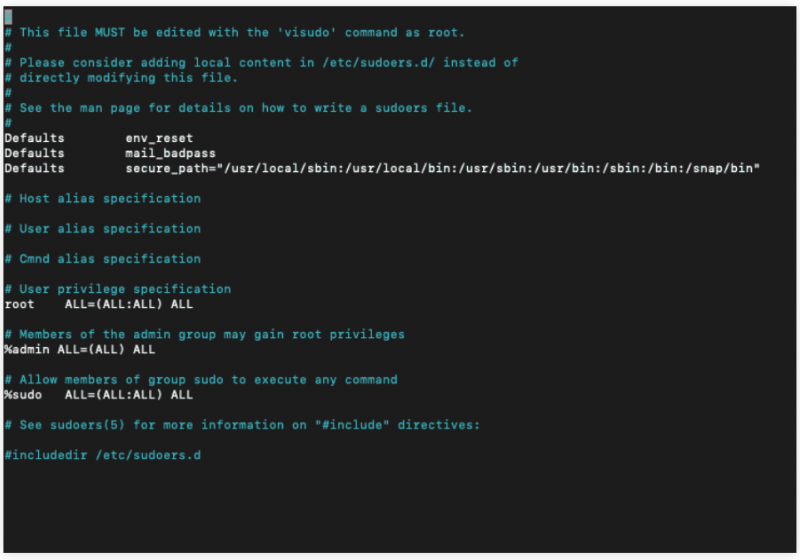

All you have to do is this:

$ rm -f /var/run/crond.pid

You should be a root user to do this.

Just that simple!

You can use one of the pre-configured cron script directories like:

/etc/cron.hourly

/etc/cron.daily

/etc/cron.weekly

/etc/cron.monthly

Just put your bash script file on any of these directories, and it will run periodically.

Description

nanosleep() suspends the execution of the calling thread until either at least the time specified in *req has elapsed, or the delivery of a

signal that triggers the invocation of a handler in the calling thread or that terminates the process.

If the call is interrupted by a signal handler, nanosleep() returns -1, sets errno to EINTR, and writes the remaining time into the

structure pointed to by rem unless rem is NULL. The value of *rem can then be used to call nanosleep() again and complete the

specified pause (but see NOTES).

The structure timespec is used to specify intervals of time with nanosecond precision. It is defined as follows:

-

struct timespec { time_t tv_sec; /* seconds */ long tv_nsec; /* nanoseconds */ }; - The value of the nanoseconds field must be in the range 0 to 999999999.

Compared to sleep(3) and usleep(3), nanosleep() has the following advantages: it provides a higher resolution for specifying the sleep

interval; POSIX.1 explicitly specifies that it does not interact with signals; and it makes the task of resuming a sleep that has been interrupted by a signal

handler easier.

How to Use the Sleep Command

To use the Linux sleep command, enter the following into the terminal window:

The above command makes the terminal pause for 5 seconds before returning to the command line.

The sleep command requires the keyword sleep, followed by the number you want to pause and the unit of measure.

You can specify the delay in seconds, minutes, hours, or days.

- s: Seconds

- m: Minutes

- h: Hours

- d: Days

When it comes to pausing a script for days, use a cron job to run the script at regular intervals, as opposed to having a script run in the background for days.

A cron job is a Linux command or script that you can schedule to run at a set time or day. These are useful for repeating tasks over a long period of time.

The number for the sleep command interval doesn’t have to be a whole number. You can also use floating-point numbers.

For example, the following syntax includes a fraction of a second:

So, what does the sleep command do in Linux?

- /bin/sleep is Linux or Unix command to delay for a specified amount of time.

- You can suspend the calling shell script for a specified time. For example, pause for 10 seconds or stop execution for 2 mintues.

- In other words, the sleep command pauses the execution on the next shell command for a given time.

- GNU version of sleep command supports additional options

- For example, suspend a bash shell script or command prompt for five seconds, type: sleep 5

- Common examples of sleep commands include scheduling tasks and delaying the execution to allow a process to start. Another usage is waiting until a wifi network connection available to stream large file over the network.

Return Value

If the nanosleep() function returns because the requested time has elapsed, its return value shall be zero.

If the nanosleep() function returns because it has been interrupted by a signal, it shall return a value of -1 and set errno to indicate the

interruption. If the rmtp argument is non-NULL, the timespec structure referenced by it is updated to contain the amount of time remaining in the

interval (the requested time minus the time actually slept). If the rmtp argument is NULL, the remaining time is not returned.

If nanosleep() fails, it shall return a value of -1 and set errno to indicate the error.

COLOPHON top

This page is part of release 5.08 of the Linux man-pages project. A

description of the project, information about reporting bugs, and the

latest version of this page, can be found at

https://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/.

2017-09-15 USLEEP(3)

Pages that refer to this page:

free(1),

gawk(1),

clock_nanosleep(2),

getitimer(2),

nanosleep(2),

_newselect(2),

pselect(2),

pselect6(2),

select(2),

setitimer(2),

fd_clr(3),

FD_CLR(3),

fd_isset(3),

FD_ISSET(3),

fd_set(3),

FD_SET(3),

fd_zero(3),

FD_ZERO(3),

__ppc_get_timebase(3),

__ppc_get_timebase_freq(3),

ualarm(3),

signal(7),

time(7)

DESCRIPTION top

Like nanosleep(2), clock_nanosleep() allows the calling thread to

sleep for an interval specified with nanosecond precision. It

differs in allowing the caller to select the clock against which the

sleep interval is to be measured, and in allowing the sleep interval

to be specified as either an absolute or a relative value.

The time values passed to and returned by this call are specified

using timespec structures, defined as follows:

struct timespec {

time_t tv_sec; /* seconds */

long tv_nsec; /* nanoseconds */

};

The clockid argument specifies the clock against which the sleep

interval is to be measured. This argument can have one of the fol‐

lowing values:

CLOCK_REALTIME

A settable system-wide real-time clock.

CLOCK_TAI (since Linux 3.10)

A system-wide clock derived from wall-clock time but ignoring

leap seconds.

CLOCK_MONOTONIC

A nonsettable, monotonically increasing clock that measures

time since some unspecified point in the past that does not

change after system startup.

CLOCK_BOOTIME (since Linux 2.6.39)

Identical to CLOCK_MONOTONIC, except that it also includes any

time that the system is suspended.

CLOCK_PROCESS_CPUTIME_ID

A settable per-process clock that measures CPU time consumed

by all threads in the process.

See clock_getres(2) for further details on these clocks. In addi‐

tion, the CPU clock IDs returned by clock_getcpuclockid(3) and

pthread_getcpuclockid(3) can also be passed in clockid.

If flags is 0, then the value specified in request is interpreted as

an interval relative to the current value of the clock specified by

clockid.

If flags is TIMER_ABSTIME, then request is interpreted as an absolute

time as measured by the clock, clockid. If request is less than or

equal to the current value of the clock, then clock_nanosleep()

returns immediately without suspending the calling thread.

clock_nanosleep() suspends the execution of the calling thread until

either at least the time specified by request has elapsed, or a sig‐

nal is delivered that causes a signal handler to be called or that

terminates the process.

If the call is interrupted by a signal handler, clock_nanosleep()

fails with the error EINTR. In addition, if remain is not NULL, and

flags was not TIMER_ABSTIME, it returns the remaining unslept time in

remain. This value can then be used to call clock_nanosleep() again

and complete a (relative) sleep.

NOTES top

If the interval specified in req is not an exact multiple of the

granularity underlying clock (see time(7)), then the interval will be

rounded up to the next multiple. Furthermore, after the sleep

completes, there may still be a delay before the CPU becomes free to

once again execute the calling thread.

The fact that nanosleep() sleeps for a relative interval can be

problematic if the call is repeatedly restarted after being

interrupted by signals, since the time between the interruptions and

restarts of the call will lead to drift in the time when the sleep

finally completes. This problem can be avoided by using

clock_nanosleep(2) with an absolute time value.

POSIX.1 specifies that nanosleep() should measure time against the

CLOCK_REALTIME clock. However, Linux measures the time using the

CLOCK_MONOTONIC clock. This probably does not matter, since the

POSIX.1 specification for clock_settime(2) says that discontinuous

changes in CLOCK_REALTIME should not affect nanosleep():

Setting the value of the CLOCK_REALTIME clock via

clock_settime(2) shall have no effect on threads that are

blocked waiting for a relative time service based upon this

clock, including the nanosleep() function; ... Consequently,

these time services shall expire when the requested relative

interval elapses, independently of the new or old value of the

clock.

Old behavior

In order to support applications requiring much more precise pauses

(e.g., in order to control some time-critical hardware), nanosleep()

would handle pauses of up to 2 milliseconds by busy waiting with

microsecond precision when called from a thread scheduled under a

real-time policy like SCHED_FIFO or SCHED_RR. This special extension

was removed in kernel 2.5.39, and is thus not available in Linux

2.6.0 and later kernels.

Description

The nanosleep() function shall cause the current thread to be suspended from execution until either the time interval specified by the rqtp

argument has elapsed or a signal is delivered to the calling thread, and its action is to invoke a signal-catching function or to terminate the process. The

suspension time may be longer than requested because the argument value is rounded up to an integer multiple of the sleep resolution or because of the

scheduling of other activity by the system. But, except for the case of being interrupted by a signal, the suspension time shall not be less than the time

specified by rqtp, as measured by the system clock CLOCK_REALTIME.

The use of the nanosleep() function has no effect on the action or blockage of any signal.

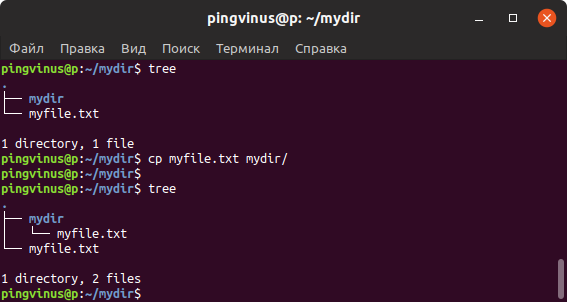

How to pause my bash shell script for 10 second before continuing

Try the read command as follows:

read -p "text" -t seconds read -p "Waiting 10 seconds for CDN/Cloud to clear cache from proxy server" -t 10 echo "Uploading a fresh version of gif file now ...." .upload.py "$gif_file" server1.cyberciti.biz |

Let’s take a look at a more advanced example of sleep

mkfifo $FIFO || exit 1

flush_and_wait | "$MYSQL" $MYSQL_OPTS &

# wait until every block is flushed #

# add sleep 1 second to slow down a bit #

while "$(echo 'SHOW STATUS LIKE "Key_blocks_not_flushed"' |\

"$MYSQL" $MYSQL_OPTS | tail -1 | cut -f 2)" -gt ; do

sleep 1

done

|

Another example that shows advanced usage of sleep command:

# workaround for a possible latency caused by udev, sleep max. 10s

if kernel_is_2_6_or_above ; then

for x in `seq 100` ; do

(exec 6<> devnettun) > devnull 2>&1 && break;

sleep 0.1

done

fi

|

Rationale

It is common to suspend execution of a process for an interval in order to poll the status of a non-interrupting function. A large number of actual needs

can be met with a simple extension to sleep() that provides finer resolution.

In the POSIX.1-1990 standard and SVR4, it is possible to implement such a routine, but the frequency of wakeup is limited by the resolution of the

alarm() and sleep() functions. In 4.3 BSD, it is possible to write such a routine using no static storage and reserving no system facilities.

Although it is possible to write a function with similar functionality to sleep() using the remainder of the timer_*() functions, such a function

requires the use of signals and the reservation of some signal number. This volume of IEEE Std 1003.1-2001 requires that nanosleep() be non-intrusive of

the signals function.

The nanosleep() function shall return a value of 0 on success and -1 on failure or if interrupted. This latter case is different from sleep().

This was done because the remaining time is returned via an argument structure pointer, rmtp, instead of as the return value.

Bash add pause prompt in a shell script with bash pause command

For example:

read -p "Press key to start backup..." read -p "Press any key to resume ..." ## Bash add pause prompt for 5 seconds ## read -t 5 -p "I am going to wait for 5 seconds only ..." |

The above will suspends processing of a shell script and displays a message prompting the user to press (or any) key to continue. The last example will wait for 5 seconds before next command execute. We can pass the -t option to the read command to set time out value. By passing the -s we can ask the read command not to echo input coming from a terminal/keyboard as follows:

function pause(){

read -s -n 1 -p "Press any key to continue . . ."

echo ""

}

## Pause it ##

pasue

## rest of script below

|

Итоги

- Bash Script Step By Step — здесь речь идёт о том, как начать создание bash-скриптов, рассмотрено использование переменных, описаны условные конструкции, вычисления, сравнения чисел, строк, выяснение сведений о файлах.

- Bash Scripting Part 2, Bash the awesome — тут раскрываются особенности работы с циклами for и while.

- Bash Scripting Part 3, Parameters & options — этот материал посвящён параметрам командной строки и ключам, которые можно передавать скриптам, работе с данными, которые вводит пользователь, и которые можно читать из файлов.

- Bash Scripting Part 4, Input & Output — здесь речь идёт о дескрипторах файлов и о работе с ними, о потоках ввода, вывода, ошибок, о перенаправлении вывода.

- Bash Scripting Part 5, Sighals & Jobs — этот материал посвящён сигналам Linux, их обработке в скриптах, запуску сценариев по расписанию.

- Bash Scripting Part 6, Functions — тут можно узнать о создании и использовании функций в скриптах, о разработке библиотек.

- Bash Scripting Part 7, Using sed — эта статья посвящена работе с потоковым текстовым редактором sed.

- Bash Scripting Part 8, Using awk — данный материал посвящён программированию на языке обработки данных awk.

- Bash Scripting Part 9, Regular Expressions — тут можно почитать об использовании регулярных выражений в bash-скриптах.

- Bash Scripting Part 10, Practical Examples — здесь приведены приёмы работы с сообщениями, которые можно отправлять пользователям, а так же методика мониторинга диска.

- Bash Scripting Part 11, Expect Command — этот материал посвящён средству Expect, с помощью которого можно автоматизировать взаимодействие с интерактивными утилитами. В частности, здесь идёт речь об expect-скриптах и об их взаимодействии с bash-скриптами и другими программами.